The Problem of Localized Ethics—An Analysis (12 November 2019) by Lawrence Davidson

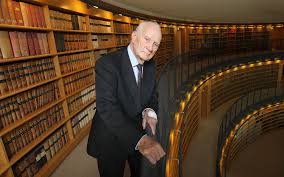

Meir Shamgar: Chief Justice of the Israeli Supreme Court from 1983 to 1995

Part I—A Local Legal Hero: Meir Shamgar

On 19 October 2019 Meir Shamgar died. He was 94 years old. Shamgar is not exactly a household name here in the West, but he was renowned in Israel. He was given a state funeral that was attended by most of Israel’s top Zionist leaders. Benjamin Netanyahu eulogized Shamgar as the man responsible for “strengthening the foundational principles of justice and the law, and guaranteeing individual and national freedoms.” Others described him as a “great man of towering intellect and deeply held ethical values.”

Shamgar reached this status and accomplished these tasks in his roles as Israel’s military advocate general, attorney general, supreme court member and then finally as the president of Israel’s supreme court. He was obviously a capable legal mind with real administrative talents. Yet, as he went about shaping Israel’s liberal-for-Jews national legal environment, he simultaneously undermined international law and human rights for non-Jews. He therefore can be seen as threatening civilized legal standards both at home and in the international arena.

Part II—The Denier of Human Rights: Meir Shamgar

Here is how Michael Sfard, an Israeli attorney who specializes in international and human rights law, describes Shamgar’s legal treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Territories: “As a judge, he handed down rulings that legalized almost every draconian measure taken by the defense establishment to crush Palestinian political and military organizations, and to establish Israeli control over the occupied people and their land for generations. Demolition of suspects’ houses (rendering their families homeless); wholesale use of administrative detentions against Palestinian activists; expropriation of lands and the establishment of settlements; undemocratic appointments of mayors; and the imposition of curfews and taxes—Shamgar sanctioned them all.”

Sfard is accurate in this description. However, he also thinks that Shamgar personifies a “paradox” that lies at the heart of Zionism—Israel’s national ideology. He tells us that this is “the paradox of a movement that is based on the moral ideal that every nation has the right to political freedom. … And yet, has denied those same freedoms to millions of people who belong to another nation.”

I am afraid Sfard has this part wrong, at least as far as the Zionist belief in a “moral ideal” that every nation has a right to freedom. There is no historical evidence that the Zionist movement ever asserted such an ideal except as a brief bit of useful post-World War I propaganda. Quite the contrary, Zionist nationalism was pursued as an extension of European colonialism. Early on Zionist leaders hitched their national ambitions (via the Balfour Declaration) to British imperialism—which, under no circumstances, espoused the national rights of the peoples they ruled. Thus, the Zionists turned on the British when they no longer needed their patronage, in order to force them out of Palestine. Just so, according to the latest biography of David Ben Gurion (Tom Segev’s A State At Any Cost), modern Israel’s founding father always understood the movement of European Jews into Palestine as one of “conquest.”

Thus, it is much more accurate to say that Zionists reserved, and still reserve, the ideal of national freedom in Palestine solely to themselves. And they do so without the “dissonance” Sfard claims is engendered by a simultaneous belief in a universal right of national freedom. Indeed, any such ideal that might support rights of any kind for the Palestinians on an equal basis with Israeli Jews is anathema to most Zionists. It is within this context that Meir Shamgar could at once be the nation’s legal hero and simultaneously deny the application of universal human rights and international law in Israel’s “Occupied Territories.”

Part III—The Broader Lesson

We can understand this disparity more broadly once we realize that ethics, or value-systems generally, are locally generated. This means that, while in principle, each value-system might have concepts such as fairness, honesty, humaneness, that have universal character, they have traditionally, that is historically, been put into practice in a more narrow way for the benefit of particular in-groups. Over time these in-groups have gotten larger until today the largest of them is now the nation state. However, the nation state has also been a source of world wars and large scale atrocities. After World War II, and the experience of a number of genocides, efforts were made to establish a set of trans-national values laid out in international law and in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was hoped that nation states could be persuaded (by the memory of the horrors of World War II, if nothing else) to adhere to humane international laws that transcended national in-groups.

Despite the historically proven fact that an in-group approach to ethics has encouraged racism and other forms of bigotry as well as horrific war, there still continues a struggle between those who would apply ethical standards universally and those who would hold to the traditional in-group exceptionalism. Meir Shamgar and the Zionists followed this latter approach.

The road they have chosen has certainly generated exclusive ethics and values reserved for just their in-group. Inevitably, this has resulted in a highly discriminatory Israeli environment which many (including some Israelis) see as creating an apartheid society. Apartheid is a form of racism recognized under international law as a crime against humanity.

The cost here is not just the injustice done to the Palestinians. There is also a serious undermining of both international law and the moral integrity of the Jewish people. One wonders if Meir Shamgar ever thought of his legal rulings and administrative reforms in this way? Or, for him, was there nothing beyond a narrow version of the ethnic nation state, where the rule of law was a sole possession of a sub-group of citizens. Of course, great men of “towering intellect and deeply held ethical values” should not think and act in such exclusionary ways. However, those who would readily sacrifice the well-being of millions do.